Up to this point we’ve talked about the high-level features of Hyperscala and have gone through a simple Hello World example, but today we’re going to write a real application to show a fairly simple real-world web application.

The real-world application we’re going to write today is a chat example. This will utilize real-time messaging, cross-session interaction, abstraction from the user-interface through DynamicContent, and much more.

We will be building upon concepts we’ve already discussed in the past two posts, so if you haven’t already read them I would recommend doing that first. I’m going to skip over the project setup and even the website configuration and focus solely on the webpage for the chat in this post.

The first thing we need to do is to create our webpage class and for the purposes of this tutorial we’ll call it ChatExample. As we can remember from previous discussion the basic setup for a webpage simply requires extending from org.hyperscala.web.site.Webpage:

Pretty simple so far. Next we are going to leverage existing HTML for the user-interface rather than writing it all in Hyperscala. This is generally the preferred route when you have a disconnect from the designer and the developer and allows for a very clean separation of duties.

The first HTML file is chat.html. It defines the form and layout of the page:

This should be put in the src/main/resources path in your project. Now, DynamicContent requires the HTML to be presented to it as a String, so we need to load and cache that HTML file:

That will load in the HTML file and store it as a String for usage in each page instance. Now lets create a DynamicContent instance in our page to load that HTML for usage and add it to the body of the page:

Now that we have the DynamicContent loaded we can extract any HTML elements we want to modify or listen to:

If you look back at the HTML file you’ll see that the Strings being supplied reference the HTML elements by id for lookup and loading. After these elements are loaded we can then modify them or even introspect the existing data from the HTML. Technically we could just load the entire HTML file and parse it as a Hyperscala structure, but that would be a waste of resources and add unnecessary complexity. By using DynamicContent we can reference only the things we care about in existing HTML and the design can change over time without any necessity of the Scala code changing (so long as those elements remain of the same type and id).

Next we need to add some real-time support to these elements so we can listen for changes and clicks:

The require call is necessary to make sure we have support for Realtime messaging. This is a Module that provides two-way communication between the server and client preferring WebSockets and falling back to long-polling AJAX. The other three lines simply connect JavaScriptEvent to the client-side corresponding JavaScript events. This will intercept client-side events of the specified type and fire them on the server as well. Note that this is simply making that occur, we now need to actually listen for the changes we’re interested in:

The above code listens for changes to chatName and updates the internal nickname. This will allow you to distinguish between who is messaging. Second, we add a ClickEvent listener to the submit button to send the message. Now lets see the body of these methods:

This method is rather simple. It calls off to our companion object calling its sendMessage method passing your nickname and the message you typed. Next it clears the value of the TextArea. Finally, it uses jQuery to request focus back to the TextArea. We’ll cover the ChatExample.sendMessage method in a minute.

First we add a nickname property to our page instance so we can reference the currently accepted nickname for this user. The updateNickname method first checks to see if the chatName has anything entered. If it doesn’t then it assigns the name ‘guest’. Next it calls off to ChatExample.generateNick with the nickname to verify that an existing nickname isn’t already present. Finally, we assign the chatName input’s value to be the newly assigned nickname.

Now we need a HTML representation of each chat entry:

We need to load the HTML again, so we add another val representing the HTML as a String in our companion object below Main:

Now we create a custom class representing an individual chat entry:

We can simply instantiate this and add it to our messages div for each message. Notice that this is very similar to our previous use of DynamicContent except this time we are extending it instead of simply instantiating it. Also, notice the use of reId = true during load of the name and body divs. This is necessary when using an item multiple times on a page as you’ll end up with duplicate HTML ids in the code if you don’t. When we specify reId = true that will simply assign a new unique id to the element at the time it loads it so each time it will be different.

Lets look at the rest of the content of our companion object now:

There’s quite a lot going on in the above code although hopefully the majority is fairly easily understood. First we see we’re keeping a history of all the messages so when a new person joins they get to see what’s already been said. The instances method gives us a peek into the powerful session framework to look up all of the ChatExample pages across all sessions on the site. The generateNick method takes the supplied nickname and checks to see if it’s already in use. If it is then it will add an increment to the end until an available nickname is found. Finally, sendMessage broadcasts the message to all pages adding a ChatEntry in their context. It is necessary to mention context at this point. For many of the underlying features of Hyperscala events and other information are localized to a page so in order to invoke changes across multiple pages we must work within that pages’ context. As you can see it is incredibly easy to contextualize to the page by simply calling the context method and passing a function to be invoked within the context.

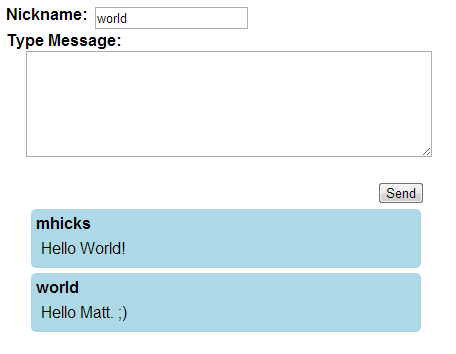

We have covered a very broad scope of functionality in this post but hopefully it was all clear and understandable. The end result should look like this:

All of the source referenced in this tutorial can be found in the GitHub repository: